TriFlower new type foramen ovale obturator

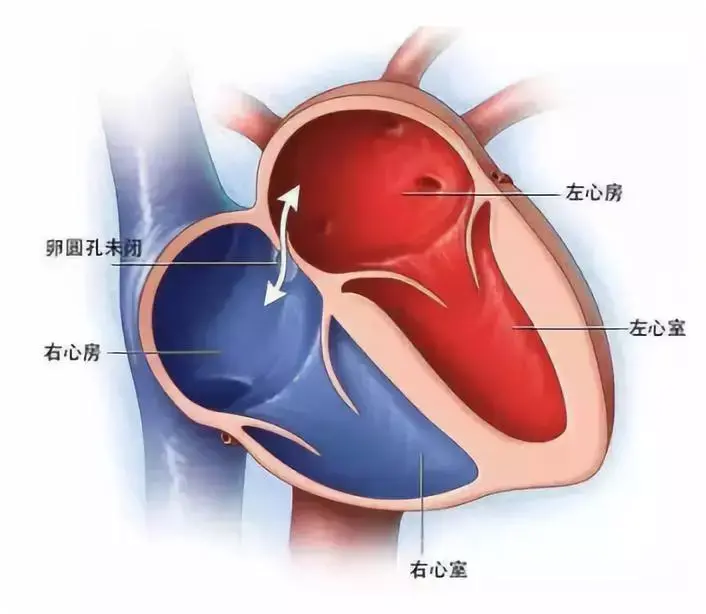

一、Patent foramen ovale

In the fetal stage of development, the foramen ovale, a communication pathway between the left and right atria, naturally remains open, allowing blood to bypass the systemic circulation. Typically, this foramen closes within the first year of life. If it persists beyond the age of 3, it is referred to as a patent foramen ovale (PFO), with an estimated detection rate of approximately 25% in adults [1,2]. Under normal circumstances, PFO typically remains asymptomatic. However, when chronic right atrial pressure rises or there is a sudden increase in right atrial pressure exceeding that of the left atrium, the naturally thin primary septum, resembling a functional valve on the left side, is pushed aside, leading to right-to-left shunting (RLS). RLS is considered the pathological basis for potential complications associated with PFO [3,4].

二、Complications of PFO

- Paradoxical embolism

RLS can lead to the migration of various types of emboli within the venous system, entering the left atrium through a patent foramen ovale (PFO), subsequently causing abnormal embolism in cerebral and/or other arteries. According to Hommea et al., the incidence of PFO in patients with unexplained cerebral embolism is 39.2%, whereas it is 29.2% in patients with a clear cause of cerebral embolism, with larger PFOs occurring at rates of 20.0% and 9.7%, respectively (P<0.05) [5].

In a study by Lamy et al., involving 581 patients with unexplained cerebral embolism, 267 were found to have PFO. Notably, the PFO group was younger than the non-PFO group, and the incidence of traditional stroke risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking was lower. This suggests that PFO-induced paradoxical embolism is one of the significant causes of ischemic stroke [6].

In fact, as far back as 1985, researchers employed cardiac ultrasound technology to identify thrombosis at the PFO site. The clinical detection of thrombosis in this location remains quite rare, and even in cases where no thrombosis is observed, the possibility of paradoxical embolism cannot be entirely eradicated [7].

- Cryptogenic stroke

Approximately 40% of ischemic stroke patients in China undergo extensive examinations without identifying a clear etiology, a condition known as cryptogenic stroke (CS). Numerous studies have firmly established a strong association between Patent Foramen Ovale with Right-to-Left Shunt (PFO-RLS) and CS.

Lechat et al. conducted an early correlation study, revealing a PFO detection rate of 21% in stroke patients under 55 years old with identifiable causes, 54% in those with unclear causes and devoid of risk factors, and 10% in those without CS [8]. Concurrently, another study in the same year examined the incidence of PFO in young stroke patients. This study found that among ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) patients under the age of 40, the rate of PFO combined with RLS was 50%, whereas it was only 15% in the control group [9]. An increasing number of scholars consider PFO a pivotal contributor to CS, constituting an independent risk factor. It's possible that PFO may be implicated in 40-50% of young patients with CS. A meta-analysis of 29 cohort studies found that 27 of them demonstrated a significant association between PFO and CS. The incidence of PFO among CS patients is three times higher than that of stroke patients without PFO [10]. The primary obstacle to supporting PFO and CS studies may stem from the relatively low probability of recurrent stroke events, which can be challenging to detect even when there's an elevated risk.

- Migraine

The exact etiology of migraine in conjunction with patent foramen ovale (PFO) remains uncertain, potentially stemming from the influx of vasoactive agents and/or microemboli into the circulatory system via PFO [11]. Multiple investigations have scrutinized the PFO-migraine nexus. Anzola et al. conducted a case-control study deploying Contrast transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) foaming test on a cohort encompassing 113 individuals with migraine with aura, 53 patients with migraine without aura, and 25 healthy controls. Outcomes unveiled a markedly elevated incidence of right-to-left shunting among patients with migraine with aura at 48%, in stark contrast to 23% (OR=3.130, P=0.002) for those with migraine without aura and 20% (OR=3.660, P=0.010) for the control group [12]. Between 22% and 38% of PFO-afflicted patients experience migraines, with 27% to 71% facing migraines with aura, significantly surpassing the general population's prevalence [13-16]. Nevertheless, divergent viewpoints exist regarding the PFO-migraine interplay. A meta-analysis, encompassing 37 clinical studies, failed to furnish substantiated proof of a causal association between migraine and PFO [17]. Ueno et al. contended that PFO solely correlates with migraine when concomitant atrial septal aneurysm is present [18]. In China, several studies have probed the correlation between PFO closure and migraine. For instance, Du Yubin et al.'s findings demonstrated an impressive migraine relief rate of 86.6% post-PFO closure [19]. Xiao Jiawang et al. evaluated the clinical efficacy of transcatheter PFO closure in migraine treatment, disclosing that 80.5% of patients reported substantial relief in migraine symptoms 12 months post-surgery, underscoring the effectiveness of PFO closure in alleviating migraine [20].

三、PFO treatment

Treatment alternatives for symptomatic patent foramen ovale (PFO) patients include pharmaceutical treatment, surgical interventions, and interventional closure therapy.

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal pharmacological intervention for patent foramen ovale (PFO) treatment, and there is no substantial disparity in therapeutic outcomes between anticoagulants and antiplatelet medications [21]. Based on physiological mechanisms, anticoagulation may offer advantages over antiplatelet therapy, because anticoagulation helps prevent thrombosis in venous stasis. However, existing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy have not definitively established the superior treatment regimen and have indicated that anticoagulant therapy carries a higher bleeding risk compared to antiplatelet therapy. Reports suggest that anticoagulant therapy may bring about bleeding complications at an annual rate ranging from 1.8% to 4.8%.

While surgical intervention has proven effective in PFO treatment, thoracotomy presents significant trauma and potential complications, including atrial fibrillation, pericardial effusion, postoperative bleeding, infection, and complications following pericardiotomy. Moreover, some patients may still face the risk of recurrent stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) after surgery, rendering this approach less favored for PFO treatment.

Numerous occluder-based treatments have been introduced for PFO management. Bridges et al. pioneered interventional PFO closure to prevent recurrent strokes, with three-year follow-up data suggesting that over 90% of patients remained free from cerebral embolism [22]. A meta-analysis revealed a relatively low stroke recurrence rate in middle-aged patients (0.47%) following percutaneous and transcatheter PFO closure in 3819 individuals [23]. Furthermore, an RCT conducted a direct comparative evaluation of three commonly used occluders in the market (Amplatzer, StarFlex, Helex), with five-year follow-up data demonstrating that PFO closure effectively reduces recurrent cerebral embolism events and Amplatzer PFO occluder showing superior performance compared to the other two devices [24]. Many clinical studies have validated the safety and efficacy of PFO closure in preventing recurrent cerebral embolic events.

At present, there have been six global-scale randomized trials comparing the efficacy of PFO closure with individual pharmaceutical treatments. Among these, only four studies have affirmed the superiority of interventional PFO closure over drug therapy alone in reducing recurrent stroke incidents in patients with concomitant PFO. These findings furnish robust clinical evidence, exemplified by the RESPECT, REDUCE, CLOSE, and DEFENSE trials [25-28].

References

[1] PAN Jiajun,ZHAO Jianrong,LV Ankang. Research progress on patent foramen ovale and migraine[J]. Internal Medicine Theory and Practice. 2009, 4(04): 334-337.

[2] ZHANG Qiang,LUO Guogang. Research progress on the association between white matter lesions in migraine and patent foramen ovale[J]. Chinese Journal of Modern Neurological Diseases. 2014, 14(09): 828-831.

[3] ZHENG Qinghou, ZHU Xianyang. Diagnosis and treatment of patent foramen ovale[J]. Journal of Interventional Radiology. 2008, 17(7): 527-531.

[4] GUO Jenny, XING Yingqi, LIU J, et al. Impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation in patients with right-to-left shunt: potential mechanisms of migraine and cryptogenic stroke[J]. Chinese Journal of Stroke. 2016, 11(04): 288-294.

[5] Homma S, Sacco R L, Di Tullio M R, et al. Effect of Medical Treatment in Stroke Patients With Patent Foramen Ovale[J]. Circulation. 2002, 105(22): 2625-2631.

[6] C. Lamy M, C. Giannesini M, M. Zuber M, et al. Clinical and Imaging Findings in Cryptogenic Stroke Patients With and Without Patent Foramen Ovale: the PFO-ASA Study[J]. Stroke. 2002, 33(1): 706-711.

[7] Nellessen U, Daniel W G, Matheis G, et al. Impending paradoxical embolism from atrial thrombus: correct diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography and prevention by surgery[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985, 5(4): 1002-1004.

[8] Lechat P, Mas J E, Lascault G. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke[J]. THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE. 1988, 318(1): 1148-1152.

[9] Webster M W I, Smith H J, Sharpe D N, et al. Patent foramen ovale in young stroke patients.[J]. THE LANCET. 1988, 1(1): 11-12.

[10] Mattle H P, Meier B, Nedeltchev K. Prevention of stroke in patients with patent foramen ovale[J]. Int J Stroke. 2010, 5(2): 92-102.

[11] Del Sette M, Angeli S, Leandri M, et al. Migraine with Aura and Right-to-Left Shunt on Transcranial Doppler: A Case-Control Study[J]. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 1998, 8(6): 327-330.

[12] Anzola G P M, Magoni M M, Guindani M M, et al. Potential source of cerebral embolism in migraine with aura : A transcranial[J]. Neurology. 1999, 52(1): 1622-1625.

[13] Azarbal B T J S W. Association of interatrial shunts and migraine headaches: impact of transcatheter closure[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45(1): 489-492.

[14] Reisman M, Christofferson R D, Jesurum J, et al. Migraine headache relief after transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005, 45(4): 493-495.

[15] Dubiel M, Bruch L, Schmehl I, et al. Migraine Headache Relief after Percutaneous Transcatheter Closure of Interatrial Communications[J]. Journal of Interventional Cardiology. 2008, 21(1): 32-37.

[16] Butera G, Agostoni E, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Migraine, stroke and patent foramen ovale: a dangerous trio?[J]. Journal of cardiovascular medicine (Hagerstown, Md.). 2008, 9(3): 233-238.

[17] Davis D, Gregson J, Willeit P, et al. Patent Foramen Ovale, Ischemic Stroke and Migraine: Systematic Review and Stratified Meta-Analysis of Association Studies[J]. Neuroepidemiology. 2012, 40(1): 56-67.

[18] Ueno Y, Shimada Y, Tanaka R, et al. Patent Foramen Ovale with Atrial Septal Aneurysm May Contribute to White Matter Lesions in Stroke Patients[J]. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010, 30(1): 15-22.

[19] DU Yubin, ZHANG Hongwei, XIN Kai, et al. Clinical efficacy of occlusion in patients with patent foramen ovale complicated with migraine[J]. Journal of Practical Medicine. 2019, 35(05): 776-778.

[20]XIAO Jiawang, WANG Qiguang, GENG Jingsong, et al. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale in the treatment of migraine[J]. Chinese Journal of Interventional Cardiology. 2019, 27(06): 303-308.

[21] Carlos J. Rodriguez M M, Shunichi Homma M. Patent Foramen Ovale and stroke[J]. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2003, 5(1): 233-240.

[22] Bridges N D, Hellenbrand W, Latson L, et al. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale after presumed paradoxical embolism[J]. Circulation (New York, N.Y.). 1992, 86(6): 1902-1908.

[23] Gafoor S, Franke J, Boehm P, et al. Leaving No Hole Unclosed: Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion in Patients Having Closure of Patent Foramen Ovale or Atrial Septal Defect[J]. Journal of Interventional Cardiology. 2014, 27(4): 414-422.

[24] Hornung M, Bertog S C, Franke J, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing three different devices for percutaneous closure of a patent foramen ovale[J]. European Heart Journal. 2013, 34(43): 3362-3369.

[25] Brauser D. RESPECT 10-Year Data Strengthens Case for PFO Closure After Cryptogenic Stroke[J]. Medscape. 2015, 1(1): 1-3.

[26] Lars Søndergaard M D S E. Patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017, 377(1): 1033-1042.

[27] J. L. Mas G D B G, O. Detante C G S C, E. Robinet-Borgomano D S J C, et al. Patent Foramen Ovale Closure or Anticoagulation vs. Antiplatelets after Stroke[J]. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017, 377(11): 1011-1021.

[28] Lee P H, Song J, Kim J S, et al. Cryptogenic Stroke and High-Risk Patent Foramen Ovale: The DEFENSE-PFO Trial[J]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018, 71(20): 2335-2342.

Pursue further excellence!